Water, Sand, and Ancient Mesopotamia

When we visited the Morgan Library & Museum, they were hosting a number of exhibitions. The first we saw was “Ashley Bryan & Langston Hughes: Sail Away.” Ashley Bryan was a children’s book illustrator who focused his work on books that celebrated Black life and creativity. He was born in Harlem in 1923 and was raised in the Bronx. He grew up surrounded by art and music, and his father worked as a printer of greeting cards, and was a lover of birds, which he kept in the family home.

WWII erupted while Bryan was completing his college education, and he was drafted into the U.S. Army. He later studied at the Columbia University School of General Studies in NYC, the University of Marseille at France, and the University of Freiburg in Germany. He passed in 2022.

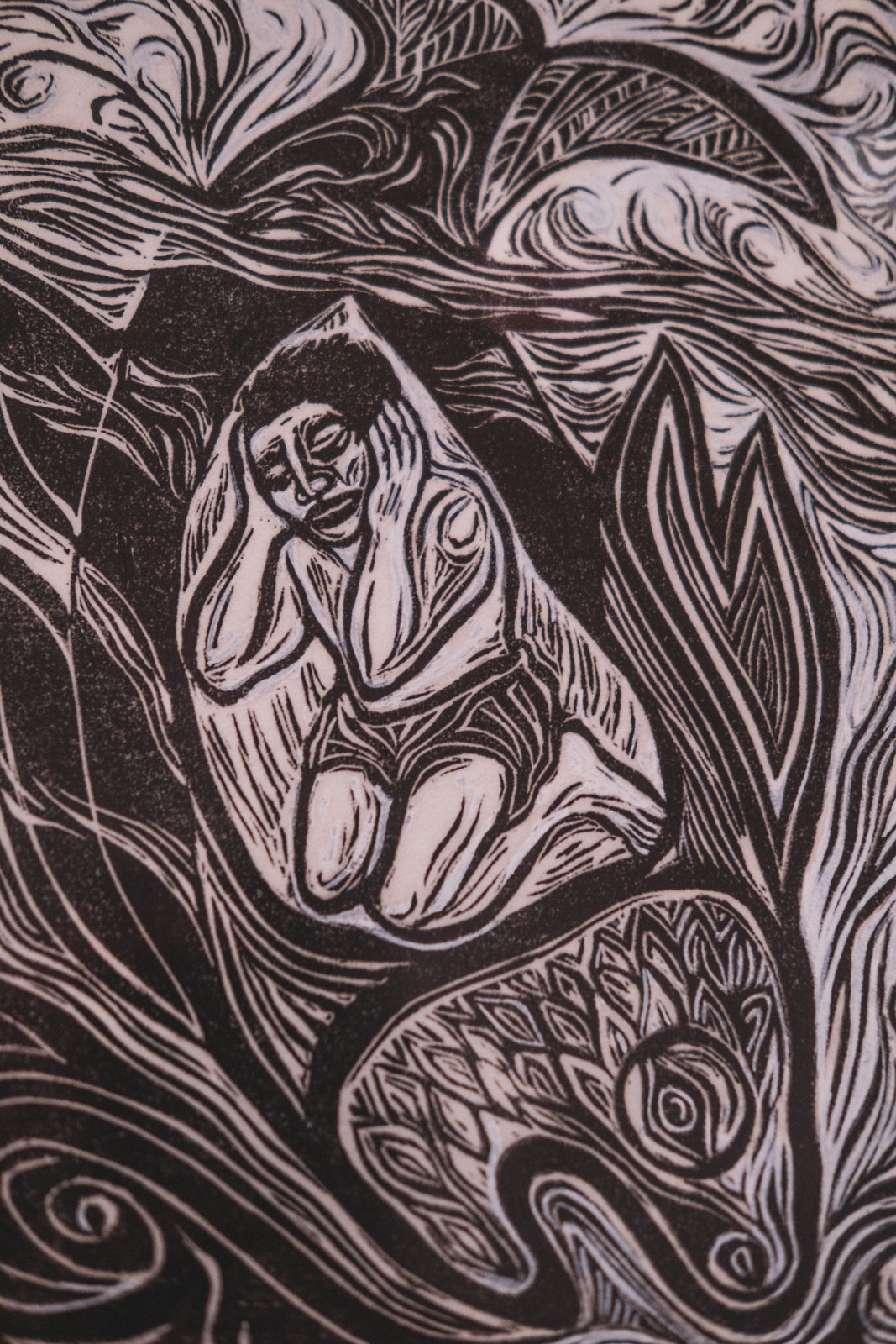

This exhibition focused on his 2015 book, Sail Away, which revolved around water, and which he paired with poems by Langston Hughes around the same subject.

Langston Hughes was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. He was prominent in a poetry style known as “Jazz poetry,” due to its rhythm and feeling of improvisation, as well as a leader of the Harlem Renaissance. Hughes was raised mostly in Lawrence, Kansas with his grandmother, Mary Patterson Langston, who instilled in him a sense of racial pride. He later attended Columbia University, where his father covered the tuition in exchange for Hughes studying engineering. He ended up leaving in 1922 due to the racial prejudice he suffered while there, and eventually got his degree from Lincoln University in 1929. He passed in 1967.

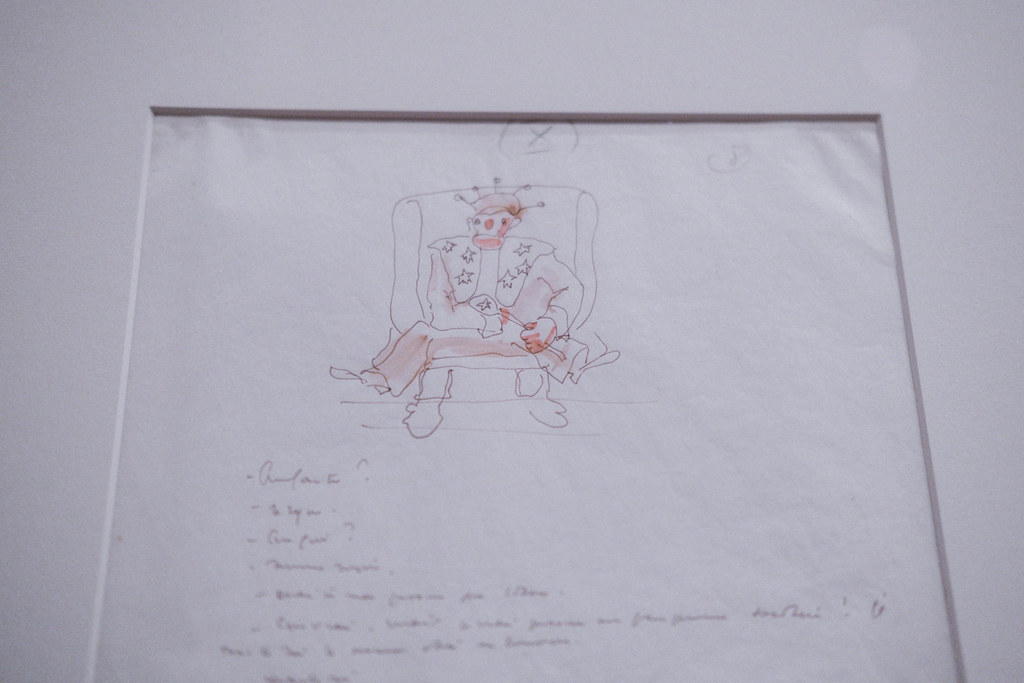

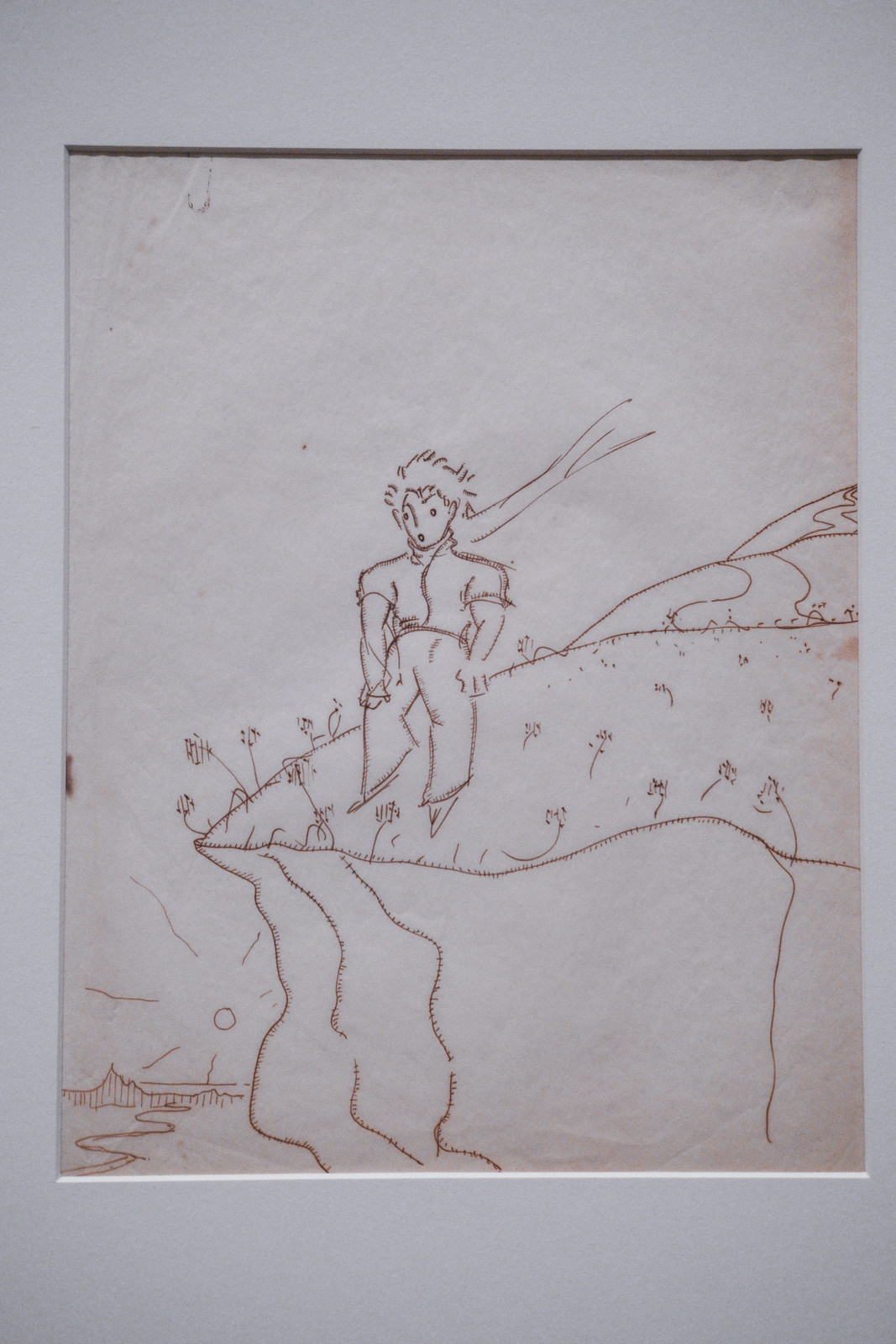

You may or may not know this about me, but The Little Prince is my absolute favorite book in the world. Its author, Antoine Saint-Exupéry, was born in Lyon, France in 1900, and was a writer, poet, journalist, and aviator.

He moved to the United States after France reached an armistice with Germany in an attempt to get them to join the WWII efforts. While there, he kept sketching a “little gentleman” around the margins of his papers, and Silvia Hamilton, an American journalist and friend of Saint-Exupéry’s, pushed the author to feature him in a children’s book — and so The Little Prince was born.

It was published in the US in early 1943, in both English and French, but would only be published in his native France after the war had ended.

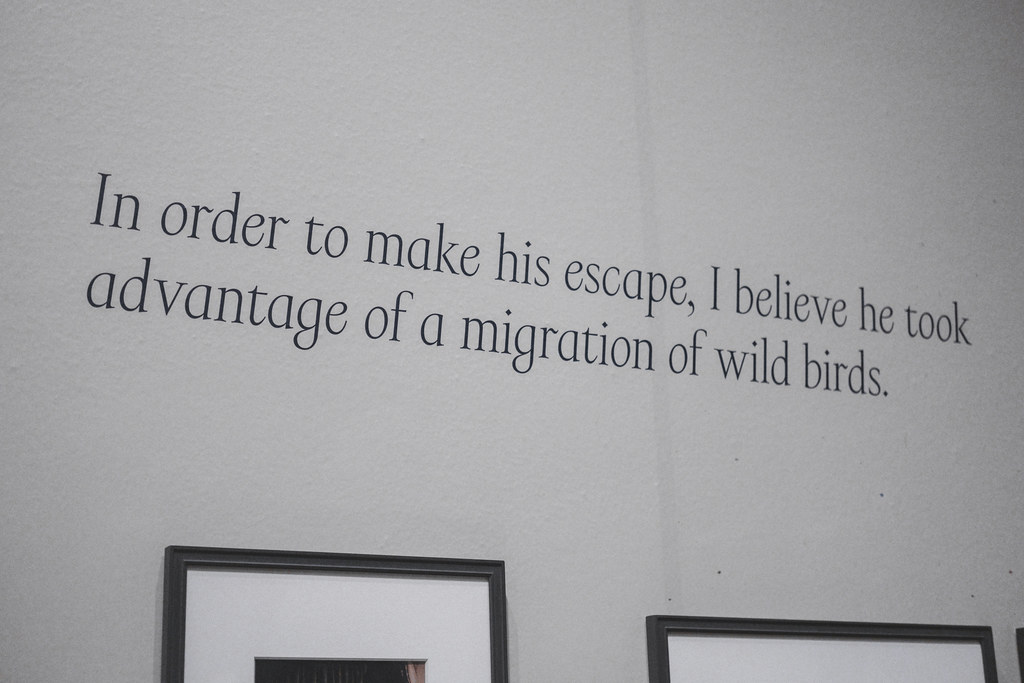

Later that year, Saint-Exupéry left the US to join the Free French Air Force. On July 31, 1944, he took off for what would be his last mission. He never returned, and the wreckage of his plane wasn’t found until 2000, off the coast of Marseille.

The Morgan Library & Museum acquired the original manuscript and art for The Little Prince in 1968 from Hamilton, who had received it directly from Saint-Exupéry when he departed for France.

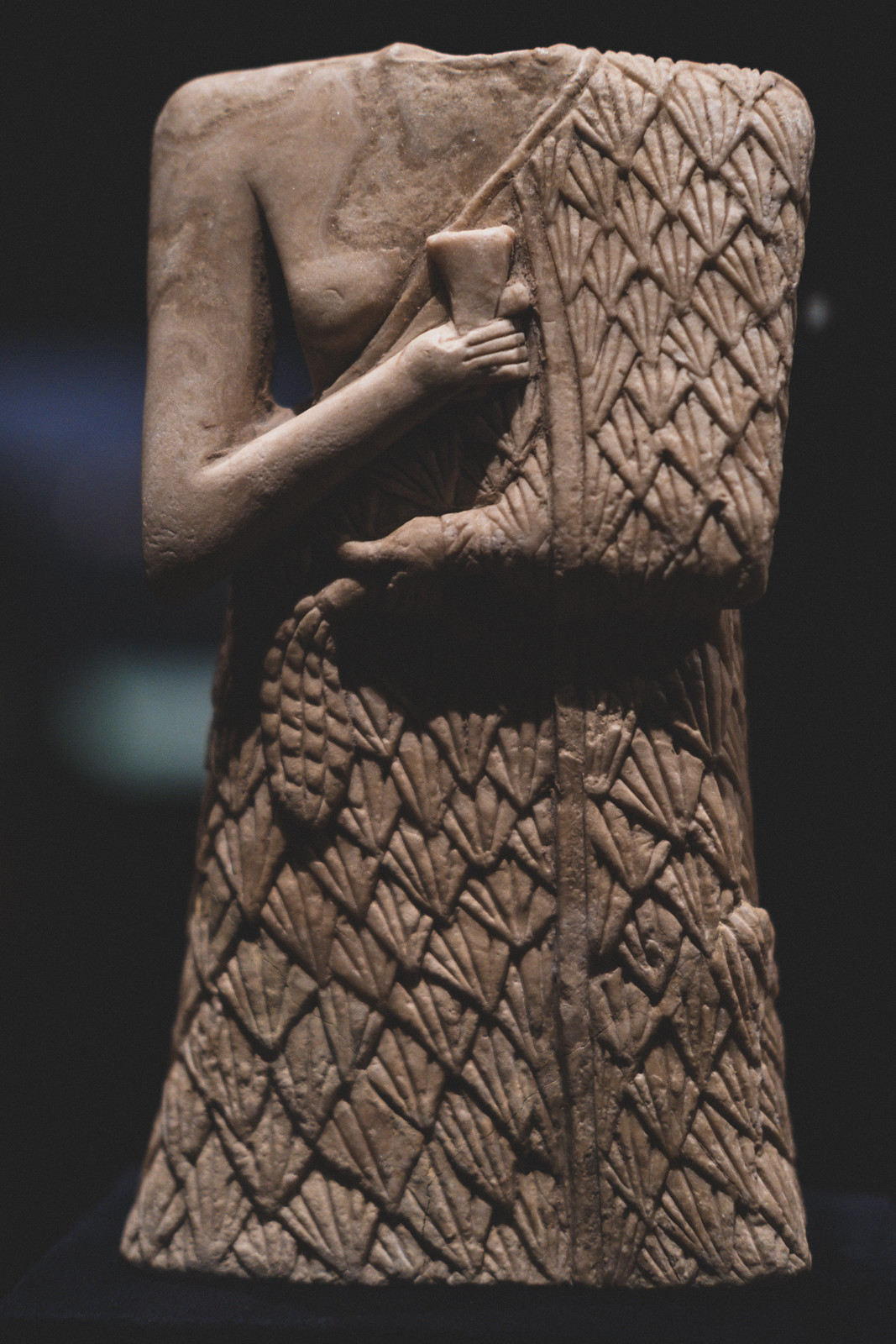

“She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia” focused on artworks that captured and reflected the lives of women in ancient Mesopotamia, in the 3rd century BCE. It focused on their roles as goddesses, priestesses, and worshippers, as well as mothers, workers, and rulers.

Enheduanna, who is named specifically in the exhibition title, was a high priestess of the moon god Nanna, as well as a poet in the city-state of Ur while her father, Sargon of Akkad, was king. She is the earliest-named author in world literature.

Queen Puabi’s headdress is a Mesopotamian crown made sometime in 2600-2450 BCE out of gold leaf wreaths, strands of lapis lazuli, and carnelian beads. It was discovered resting on Queen Puabi’s remains during the excavation of the Royal Cemetery at Ur in 1922-1934, untouched from the moment of burial.

Her seals do not place her in relation to any king or husband, so it is theorized that she ruled in her own right, though it has also been suggested that she was the second wife of King Meskalamdug.