Nightshade and Old Lace

Bard Graduate Center

The Bard Graduate Center in New York City is attached to Bard College, hosting exhibitions and public programs concerning material culture. When I visited, the gallery was hosting an exhibition called Threads of Power, showcasing lace from the Textilmuseum St. Gallen, located in St. Gallen, Switzerland.

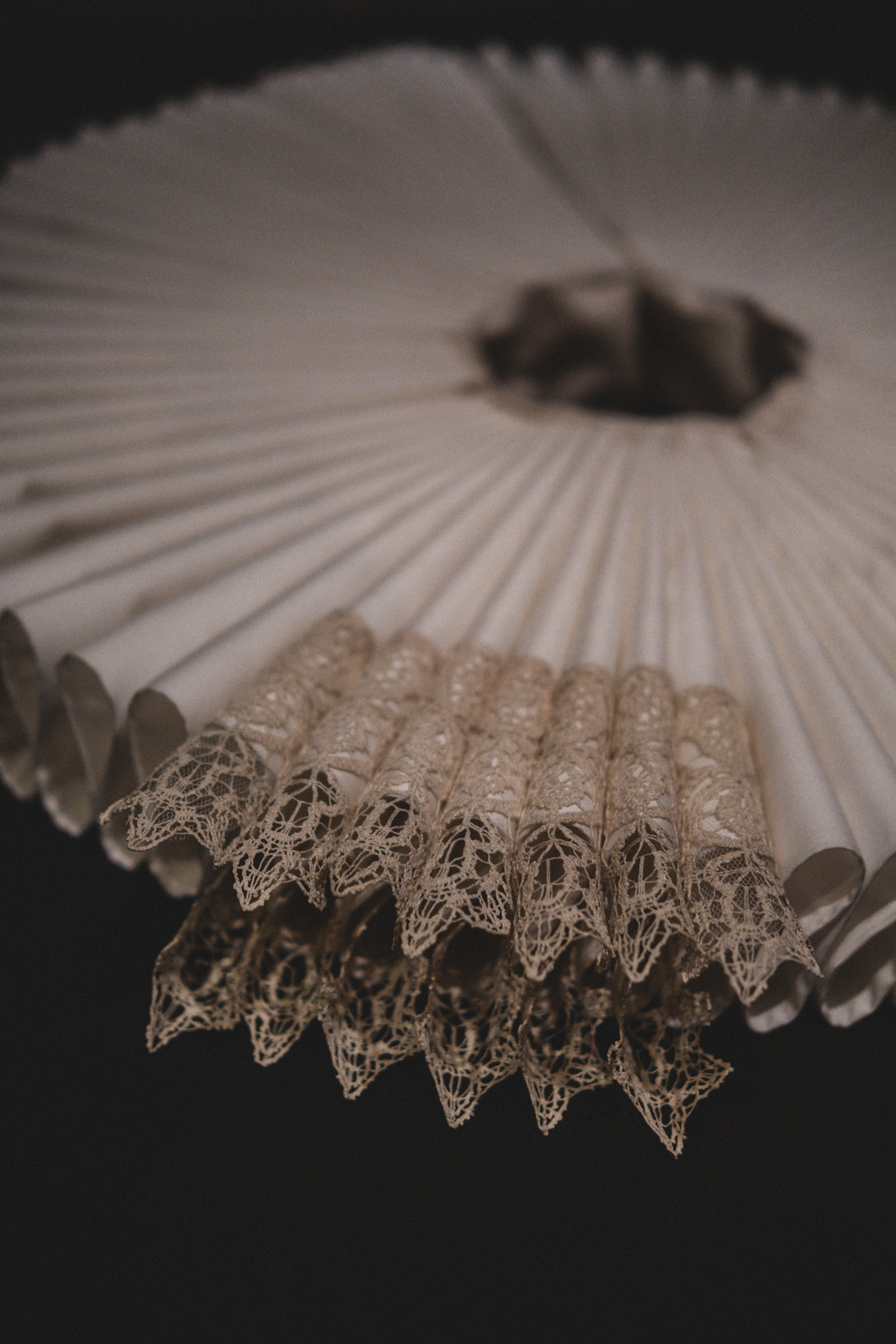

Its objects illustrated the history of lace, from its origins in the sixteenth century, to the present day. The word lace may come from Middle English, the Old French word for noose or string, las, or the Vulgar Latin for noose, laceum, similar to lacere, to entice or ensnare.

Some believe lace originated in Italy in the 1500, but as it so often happens with such widespread inventions, this is heavily disputed. It was an important Venetian export in the 16th and 17th centuries, where its most important patrons were the nobility and aristocracy. Belgium and Flanders were also known as major centers for its production, primarily bobbin lace, holding an industry for handmade lace that still exists today.

Lace seems to have arrived in France by way of Catherine de Medici, who married King Henry II in 1544. In Spain, Point d’Espagne lace, which was made of gold and silver thread, was much in use in churches and for the mantilla (a veil worn over the head and shoulders). Barbara Uttmann is considered to be one of the greatest producers of lace in Germany, where she started a workshop in Annaberg in 1561. By the time of her death in 1575, there were over 30,000 lacemakers in her area.

A costly product, only the wealthiest members of society were able to wear it, which is not to say that those who produced it were wealthy themselves. Its artisans were often people of lower classes attached to noble houses, or unmarried girls sent to convents to be come nuns and work for weeks or months (or sometimes years!) to produce the pieces you see here.

The beginning of the exhibition did an excellent job of making it clear just how difficult lacemaking can really be… all the more reason to be thoroughly impressed by the objects shown in the rest.

Originally, linen, silk, and gold or silver threads were used, whereas nowadays lace is usually made of cotton, linen, and synthetic fiber. In the wake of the French Revolution, machine-made lace became a thing, so that it became more accessible to the growing middle class, as well as mostly a female-fashion feature. By the end of the 19th century, this new kind of lace dominated the market.

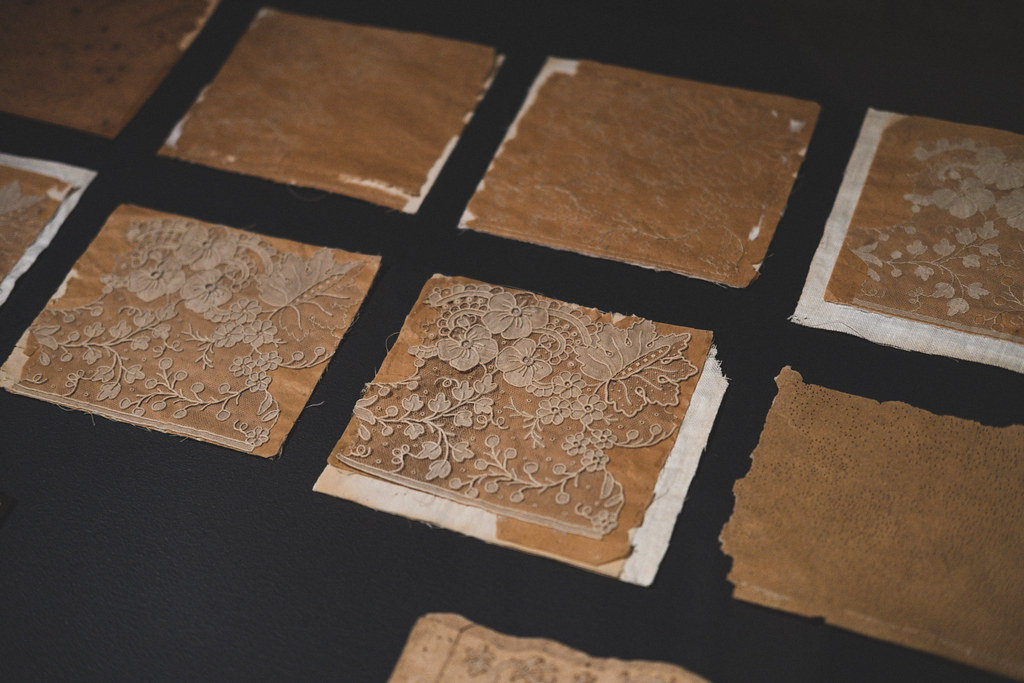

In the 1880s, “chemical lace” appeared on the market. This type of lace is made by embroidering a pattern on a piece of fabric that has been chemically treated to disappear after the pattern has been created, imitating the look of real handmade lace. This allowed the industry to expand, and while areas of Austria and Germany were prominent in the field, St. Gallen was the world leader for machine-embroidered products.

Post-WWI, however, the industry faced a steep decline, as the “extravagance” of lace was left behind. In the second half of the 20th century, there was a resurgence in the use of lace for high end fashion brands, including Christian Dior, Yves Saint Laurent, and Gianni Versace.

You can read much more about this exhibition, and the history of lace, here.

Isn’t this bouquet just perfect for Halloween? While it looks like tiny pumpkins, the solanum aethiopicum, or Ethiopian eggplant, is actually that — a decorative eggplant. It originates in Asia and Tropical Africa, and is also colloquially known as Ethiopian Nightshade, pumpkin-on-a-stick, and bitter tomato.